Loch Morar Expedition Report 1975

© Shine.

May be used for private research only. All

other rights reserved.

This

year an attempt was made to investigate the

cause of sightings indicating the presence

of a large unknown animal in Loch Morar, with

characteristics similar to those familiar

at Loch Ness.

The

following report is to record this, since

though we have failed so far, there are elements

in our objectives, attitude and method, which

are new to investigations of this kind. Furthermore,

we have broken ground along our chosen lines

of approach, and so have confidence in seeking

support for a continuation and extension of

our activities next year.

The

expedition took place between August 15th

and the end of September and consisted mainly

of zoology students of Royal Holloway College,

University of London, who manned the equipment

which I had designed and built in collaboration

with Mr. Trevor Wicks.

Expedition

Members

M.

Barrett

L. Davis

I. Ericke

D. Foakes

P.

Kennedy

T. Leighton

I. Montgomery Campbell

G. Orton

T. Parker

M. Parsons

C. Penfield

|

S. Robinson

J. Saye

D. Sharp

D.Shirt

N. Smith

A. Thorogood

R. White

M.

Whitehead

T. Wicks

A. Wyatt |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We

wish to express our gratitude to the following

for their co‑operation encouragement:

Mr.

Tim Dinsdale, A.R.AeS

The

Loch Morar Survey. 1970-72

Elizabeth

Montgomery Campbell, MJI

Dr.

David Solomon

The

Master of Lovat

The

residents of Morar, particularly Mr. McCleod

(proprietor of the Morar Hotel) and

Mr.

Walker, Mr. Angus Cameron, Mr. Morrison and

Mr. Mc.Donnell

.

We

also record our appreciation of the help given

to us by the following in contributing equipment

free of charge, especially to Stanmore Video

Services Ltd. for providing a closed-circuit

television system.

Gwelo

Manufacturing Ltd

Mr.

Tony Dodds

Mr.

R. Pliskin

Electronic

Pest Control Ltd.

Scientific

& Technical Ltd.

Admiralty

Research Laboratory

Drawings

by MJ. Parsons

Published

November 1975, Loch Morar Expedition 1973-75

GENERAL

DESCRIPTION

Loch

Morar is a glaciated fresh‑water lake,

lying about 2.5 miles south of Mallaig, on

the south‑west seaboard of Inverness-shire. It

is some twelve miles long, with an average

width of nearly a mile, and has a catchment

area of about 65 square miles. The area is

one of metamorphosed Moine schist, with drowned

fjord‑like valleys, deepened by the

glaciers. The Loch is typical of lakes formed

in this way, having a great depth at the centre,

while being shallow at the seaward end. Here

there is a low‑lying area, known as

the "Smooth Mile", which is a terminal moraine

and upon which the present village of Morar

stands. At this point the very short River

Morar drains the loch into the sea only a

quarter of a mile away, with a fall of only

thirty feet. It is believed that the sea level

was once higher, just as the ice retreated

and that 6000 years ago, there would have

been little difference between loch and sea

level. This would have made it easier for

marine animals to enter.

The

lake is the deepest in the British Isles,

the maximum recorded depth being 1017 feet

in the centre, opposite the River Meoble,

one of the main feeder streams of the southern

shore. To find an equivalent depth in the

sea, west of Scotland, it is necessary to

go beyond the continental shelf west of Ireland.

Though a third deeper than Loch Ness (which

is a fault line) Morar is less steep‑sided,

having a mean depth of only 284 feet as against

433 feet. It has a much greater proportion

of shallow water and many small shallow bays,

particularly to the south.

This

is important, as bottom fauna, the main food

for fish, is restricted to water less than

50 feet deep and Morar is therefore relatively

productive in a biological sense. There are

substantial numbers of salmon, sea‑trout,

brown trout, char, eels, sticklebacks and

minnows. It may be of significance that salmon

only enter the Loch to spawn, having derived

the energy for their development from the

sea. They could therefore be an important

food source independent of the basic productivity

of the loch. There is now a hydro‑electric

power dam on the River Morar, which would

effectively prevent any large animal leaving

the loch by that route. The village of Morar

lies at the western end on the "Road to the

Isles" but is screened from the greater

part of the loch by hills and a group of wooded

islands. A road runs to the village of Bracorina,

about one third along the length of the loch.

Only the few houses of this village and a

house at Swordlands overlook the water. Compared

with Loch Ness therefore, very few people

are in a position to see the loch's surface.

INTRODUCTION

The

object of this expedition has been to establish

the identity of the large unknown animal of

the Scottish lochs, evidence for the existence

of which has already been adequately assembled. After the years

of reliable eye‑witness accounts, sonar

and photographic evidence none can presume

to "discover" the Loch Ness Monster.

Indeed, I feel that further efforts aimed

merely at collecting evidence for its presence

will be labouring the point and could lead

to a crusading but defensive spirit, likely

to alienate those to whom such evidence is

submitted. However, in the continued absence

of official interest, the amateur naturalist

has the opportunity, actually to establish

of what kind the creature may be. Should the

Loch Ness Monster come to be universally accepted

it will be largely through the efforts of

amateurs; there is no presumption in attempting

to finish the job.

To

a great extent, the opaque, peaty waters of

Loch Ness have forced investigators to concentrate

upon a surface watch for what is obviously

an aquatic animal. This has resulted in very

infrequent observations at long range of a

very small portion of the creature. More logical

underwater methods have been largely discredited

through ambiguities in interpreting the results.

Obviously, sonar traces are particularly difficult

to analyse, whilst even underwater photography,

due to the necessity for "computer improvement",

produces indecisive results. Direct observation

within the creature's own element is very

difficult at Ness due to the colloidal peat

stain drastically restricting visibility.

Ironically

therefore, I believe, it is partly the concentration

of effort and resources on Loch Ness, which

has delayed progress so long. Firstly, the

notoriety attaching to Ness detracted from

the value of reports from elsewhere and by

branding the creature as a unique phenomenon,

made its acceptance less probable. Then the

basic water properties of Loch Ness imposed

limitations of technique, leading to inconclusive

results.

Of

the reports from other lochs, those from Loch

Morar are the best documented, due to the

work of the Loch Morar Survey, which has over

three years, collected some 38 sighting reports,

in addition to valuable biological data. Three

of these sightings were by their own members.

Reports from Morar go back over a hundred

years and refer to a beast recognized by local

tradition as the "Mhorag". When

seen this was considered an omen of death

for a member of one of the clans living by

the loch. All the features of the descriptions

tally with the reports from Loch Ness. The

Loch Morar Survey concluded that the loch

did hold a genuine mystery justifying investigation.

By

far the most significant relevant difference

between Ness and Morar is water clarity, Loch

Morar having a clarity exceptional in the

British Isles. Three eye witnesses report

seeing the creature underwater. Here is an

opportunity to make, for the first time, a

committed and logical search within the creature's

own largely unexplored environment, with a

reasonable hope of unqualified success.

Our

expedition has used techniques specifically

exploiting water clarity to achieve direct

observation of the species underwater and

to search for actual organic remains. We are

the only British expedition to have attempted

this. Beneath the surface it will be possible

to see and photograph the animal's entire

profile, not just a series of humps to theorise

upon. This is vital to identification, as

many structural features remain unknown.

No

continuous surface watch was attempted, as

1 did not feel that even if successful, it

would contribute any further to the objective.

Again, no attempts were made to collect further

eyewitness accounts, as except insofar as

they reveal aspects of behaviour or new features,

they can only serve to reassure us. In fact,

we did receive some accounts unsolicited and

where those involved were prepared to allow

it, passed these on to the Loch Morar Survey.

The way forward is to accept the evidence

found by previous investigators and act on

it, not in duplicating it.

Though

we are logically compelled to search underwater,

it is obvious that whatever the conditions,

visibility will be very restricted. Thus it

is vital to deduce some tactical scheme of

approach.

The

possible food sources present in the loch

were fish, plankton, detritus and plants.

With the possible exception of detritus, all

these are most abundant inshore and near the

surface, within the photic zone (that depth

to which light sufficient for photosynthesis

can penetrate). The photic zone is within

some forty feet. Most aspects of structure

and behaviour so far reported indicate a fish

predator and the findings of the Biological Section of the Loch Morar Survey, confirm that there

are sufficient fish to support a population

of such predators. Evidence from both Ness

and Morar, suggests that the monster frequents

shallow bays and even that it may have well‑established

"patrol lines", which is characteristic of

predators in general. If this is so, the creature

must frequent the upper layer of water in order to find food. It is upon

this assumption that the operation has been

launched, at first on a narrow front, to explore

the shallow water.

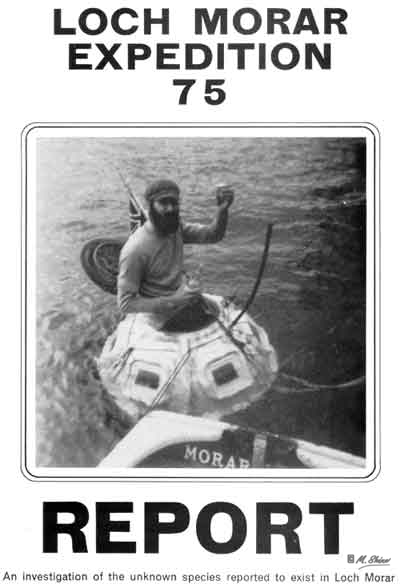

THE SUBMARINE OBSERVATION CHAMBER "MACHAN"

Objections

to the use of submarines at Loch Ness have

centred around the poor visibility under water

and the slow speed of the submarine. Small

submarines have a speed of about three knots,

while the quarry is reported to be capable

of ten times as much. All this implies an

attempted pursuit.

A

well‑proven method of observing wild

life on land is by means of a "hide". The

purpose of Machan is to provide a passive

underwater camera hide at strategic points

around the loch at a depth of about thirty

feet. When submerged she rests on the bottom

silently, without movement, and allows photography

using existing light.

Machan

consists of a forty-inch diameter fibre glass

sphere, stiffened by moulded ribs and flanges.

There are six ¾-inch plate glass ports

angled slightly upwards to gain maximum visibility

against the surface brightness. This has been

established at about sixty feet. The main

ballast is suspended in a cage beneath the

sphere. The observer sits between two water

ballast tanks inside, and submersion is achieved

by flooding these. As there are no compressible

air spaces at any time during the dive, it

is possible to make extremely fine adjustments

to trim, even to the extent of remaining stationary

at a given depth. In order to surface, water

is then pumped out with a ¾-inch bore

pump. As only just sufficient water is admitted

to take the craft down, only a small amount

need be expelled to make it ascend. Once at

the surface, freeboard is obtained by pumping

out more water with a diaphragm bilge pump

or by the surface crew removing small ballast

weights from the outside. Should the surfacing

mechanism fail for any reason, the vessel

can simply be pulled to the surface manually,

as in the submerged state it weighs only a

pound or two. In an extreme emergency, the

main ballast can be released, thus allowing

the craft to surface immediately, with an

excess buoyancy of about 900 pounds. Air is

supplied from the surface at 2 cu.ft. per

minute by means of hoses and a small electric

pump. The chamber alone contains enough air

for at least an hour. A telephone provides

communication between the observer and the

surface.

The

chamber is intended to be used in shallow

bays off the mouths of main feeder streams,

where the largest concentrations of fish

are to be found and where it can be used furthest

from the shore, while remaining in shallow

and sheltered water. A depth of thirty feet

is adequate, as it is the maximum at which

there is sufficient light for filming and

also coincides with the depth at which fish

find most of their food. The bottom fauna

is most abundant here. The Loch Morar Survey,

in analysing the behaviour of the creature,

concluded that it does appear to frequent

shallow water and particularly bays.

Operations

were limited this year by the fact that we

were unable to use the intended site. Nevertheless,

Machan has now dived some thirty times without

incident along the twenty-foot contour off

the islands, sometimes remaining submerged

for two hours. Film has been shot successfully

at this depth. When baited with a preparation

supplied by Scientific & Technical Ltd.,

the chamber is frequently surrounded with

shoals of small fish ‑ for example,

sticklebacks and fry, which remain undisturbed

and indeed show some curiosity. On one occasion

a large shoal of trout was seen. Machan, while

remaining essentially simple, is effective

through the versatility and resilience of

the human being.

VIDEO

EQUIPMENT

As

a development of the underwater vigil, we

were fortunate to receive the support of Stanmore

Video Ltd. in adapting a closed‑circuit

television system for use beneath the loch.

A camera is maintained underwater, while an

observer views a monitor screen on the surface.

This allows continuous surveillance with no

water disturbance and without the obvious

risks to life. Video equipment also has the

ability to operate at the very low light levels

found underwater and results can be seen and

recorded immediately without the need to process

films. Mounted in similar locations to those

envisaged for the manned submersible, this

equipment represented our best hope of obtaining

close‑up film.

While

being tested on the surface, the camera was

used successfully as an image intensifier

to scan the loch at dusk. During tests underwater,

the camera failed due to condensation. This

was in no way attributable to any basic inadequacy

of the system, which had impressed us greatly,

but to simple bad luck. The electrical problems

posed by using the system in the field have

been solved. It was evident that video had

the greatest potential of all the equipment

used and we still consider it to be the best

means of meeting our requirements. We shall,

therefore, be using it again next year on

a larger scale.

GLASS‑BOTTOMED BOAT PEQUOD

The

remarkable clarity of the water was further

exploited by building a specialized glass‑bottomed

boat to carry out an extensive survey of the

shallow water, in a search for organic remains

or other evidence of large creatures. The

loch lies almost parallel to the prevailing

westerly winds and a floating carcass could

have been deposited at the eastern end or

"head" of the loch. There was the fascinating

possibility of a "graveyard" within feet

of the surface, which would certainly have

remained undetected until now. Some marine

species, i.e. elephant seals, tend to form

graveyards, while dying whales have been known

to beach themselves in order to breathe. As

a very long shot indeed, and bearing in mind

the sightings from boats of the creature underwater

recorded by the Loch Morar Survey, there was

a chance that a living specimen would be seen.

The

Pequod consists of a small boat 8 ft long

with a 2 h.p. engine and a crew of two. The

observer lies face down in a central channel

9 inches below the waterline, looking through

a transparent plastic dome. This gives him

all round visibility from directly ahead

to straight down, and even a little astern.

With the head held back from the dome there

was a measure of distortion due to a "fish‑eye"

lens effect, but this in itself gave the advantage

of much more extended visibility. The maximum

range under normal conditions was probably

about 30 feet, which was confirmed by echo‑sounder.

A galvanized anchor was seen at a measured

50 feet below the surface, but this was obviously

an ideal object.

A

technique of working was evolved whereby the

craft was towed to the section to be covered

by a support boat. It them moved in and out

from the shore in parallel sweeps, with no

more than 10 feet between each. The observer

was replaced every 30 minutes. During the

survey it is calculated that the Pequod covered

some 200 miles in a thorough search of virtually

all the possible water. Although no unknown

skeletal remains resulted, this was by far

the most significant part of this year's effort,

giving us insight into the critical shallow

water contours and fish feeding grounds.

For

the most part, the bottom shelves gently to

between 20 and 30 feet, with a "scree"

of broken rocks, pebbles or sand. This often

gives way suddenly to silt, which slopes more

steeply. Plants and most of the fish seen

are confined to this 30 feet of water. The

presence of this shelf at about 20 feet would

make it possible for a large predator to patrol

the fringes of the loch in deeper water without

being seen. It may be significant that where

this ledge is absent and the slope more uniform,

i.e. Swordlands and Meoble Bays, the creature

is sometimes seen. We did find a few large

grooves or scratches in the silt about 10

feet down, but they were quite possibly caused

by items pulled by boats; nets etc.

The

shallows at the head of the loch were interesting

in that they did in fact contain a large amount

of debris in the form of decaying tree trunks.

As expected, plants were most numerous in

bays and off the entrance to the River Morar.

The south shore seemed richer in plant life,

which tended to be concentrated at the eastern

ends of the bays.

We

can say that rooted plants are unlikely to

be a food source. They are not present in

sufficient numbers and those present showed

no signs of disturbance.

Having

virtually eliminated the possibility of there

being a skeleton in the shallow water, we

shall extend our search to the deeper water.

HYDROPHONES

Through

the help of the Royal Navy, we were able to

operate a hydrophone set in an attempt to

record any unusual underwater sounds. The

system was used in a bay near the 30-foot

contour among the islands. The hydrophone

remained on the bottom about 200 feet out.

Monitoring was carried out at all hours of

the day and night. Although the equipment

was very effective, no inexplicable sounds

were heard. Experiments were conducted by

"broadcasting" unidentified sounds recorded

at Loch Ness by Bob Love. No responses were

obtained.

CONCLUSION

After

three years work, we can now claim to have

developed a satisfactory system of passive

underwater surveillance and have found the

most promising sites for its use. We hope

to give it a fair trial shortly. We have also

made a beginning upon a search for organic

remains, which will be extended to include

the deepest parts of the loch. In our view,

Morar remains the most potentially rewarding

site for active investigation. We believe

that our methods now provide the best chances

of any so far employed and shall seek support

in our intention to extend them.

ADRIAN J SHINE

Back

to the Archive Room

Loch Ness and Morar Project Report 1975 - Adrian Shine